Point of View: Stories Are About PEOPLE

Today’s guest post is by Jim Adam. It is part of a series on storytelling and The Strengths of the Potter Series. Check out Jim’s book, Motherless. The number of…

Today's guest post is by Jim Adam. It is part of a series on

storytelling and The Strengths of the Potter Series. Check out Jim's

book, Motherless.

The

number of point of view characters in a story affects the reader’s view

of how focused that story is. POV also influences the reader’s

emotional connection to characters in the story.

Stories are about

people, and the Potter series makes clear through its use of POV that

it is about Harry. Other characters, settings, hobbies, and events are

important to the story only when they are important to Harry.

Some

stories require multiple POVs, but slush-pile fiction often switches

POV inappropriately.

Consider the following synopsis, where one

sentence represents a scene or chapter in a book, and the POV character

is the subject of the sentence:

- Lisa discovers a dead body in the trunk of her car.

- Lt. Manning takes over the investigation into the mysterious corpse.

- George, Lisa’s estranged husband, has an argument with Lisa about letting strangers place dead bodies in her automobile.

- A nameless individual sits in a dark room, planning a gruesome crime.

- Dr. Trace performs an autopsy on the previously-mentioned corpse.

- Chief of Police Henries gives Lt. Manning a dressing down over poorly prepared paperwork.

- Timmy, who works at Squeaky-Clean Car Detailing, experiences emotional trauma as he cleans out the trunk of Lisa’s car.

- Alexander is jogging at night when he is attacked, kidnapped, tortured, and finally killed.

The

synopsis above is make-believe, as well as incomplete, but it fairly

represents the outline of many novels sitting in slush piles around the

world. The switching POVs aren’t the problem, but they are a symptom of

the problem. The real problem is a failure to decide what story the

novel wants to tell.

If asked to boil the above synopsis down to a

single sentence, the best we could do would be, “It’s a story about

some murders that occur within a community.”

Unfortunately, that isn’t

a story summary, it’s a premise. Stories are about people.

The above

synopsis describes a story that’s about “everybody affected by the

murders.” Unfortunately, a story about “everybody” is most likely going

to wind up feeling either scattered and unfocused, or else abstract and

experimental.

Nothing’s impossible, of course, and certainly writers

like Stephen King have achieved success with novels that feature a

large number of POV characters.

For most beginning writers, though,

trying to build a story around our synopsis would be disastrous.

The

result would lack focus, would lack literary purpose, would wear

readers out with all those POV changes, and would fail to make readers

care about key characters. As the villain from The Incredibles says,

“When everyone’s special, no one will be.”

Rowling wrote seven

books using Harry’s POV almost exclusively, and the few exceptions were

a result of necessity. The opening of Book 1, Philosopher’s Stone,

can’t be from Harry’s POV because he’s a year old. The opening of Book

4, Goblet of Fire, sets the stage for the rest of the book, and Frank

Bryce’s experiences in that first chapter directly affect Harry via his

mental connection with Voldemort. The opening of Book 6, Half-Blood

Prince, again sets the stage for the main plot line of that story. In

every case, these instances of POV switching serve a real purpose.

Using

a single, dedicated POV character brings with it many benefits, and it

is certainly one of the strengths of the Potter series.

Once

readers identify with a POV character, they’re liable to take his word

for things. If he feels he’s made a mistake, the reader will likely

agree (though they may decide that he’s being a bit hard on himself, if

he takes the mistake too personally). If he feels that he has acted

appropriately, few readers will question this, unless the POV character

has torched a puppy, or done something equally shocking and

reprehensible.

In the movie The Matrix, for example, Neo is the

primary POV character. He and his associates are set up as the good

guys, and viewers come to identify with these characters. As a result,

when the good guys go into a building and murder a bunch of police

officers, we nod our heads and agree that this is the only possible

course of action.

According to Morpheus, anyone who disagrees with

the good guys is “so hopelessly inured” to a satanic, immoral way of

life that they don’t count, and we quietly accept his description of

the situation. Killing ordinary citizens is sometimes an unfortunate

necessity, but soon the good guys will overthrow the lawful government

and replace it with one more appealing to them. Then they can instruct

people in the Right Way, eliminate any who fail to get the message, and

the one true religion will prevail.

Because we identify with Neo and

his buddies, we see in them freedom fighters rather than terrorists.

This is the (rather frightening) power that POV has.

The Potter

series uses POV and reader identification masterfully. First, readers

learn to trust Harry. While he might at times be hard on himself, and

at times might be mistaken in his judgments, in his heart he values

honesty—including self-honesty. As a result, not only do we give him

the benefit of the doubt in everything he does, but his opinion of

others greatly influences our response to those people.

Harry

reveres Dumbledore and so readers revere him—even though we don’t

really see all that much of the headmaster. Harry dislikes Snape and

Malfoy, so we dislike them as well. (Their actions reinforce our

dislike, but also reinforce our trust in Harry’s judgment.) Harry

respects Hagrid but views Dobby and Moaning Myrtle as too odd to be

taken seriously, and this shapes our opinion of those characters.

Surely Dobby isn’t any weirder than Hagrid, but is merely weird in a

different way, yet we view Hagrid as an odd fellow worthy of respect,

while we see Dobby as a silly little blighter who happens to prove

useful now and then.

By carefully controlling POV, the Potter

series gains an almost hypnotic power over its readers, and it uses

this power gleefully to keep readers in its thrall. Luckily, the

series’ goal is to entertain, and most people get their soul back as

they exit the tent.

Next in series: Plot-Defining Disturbance

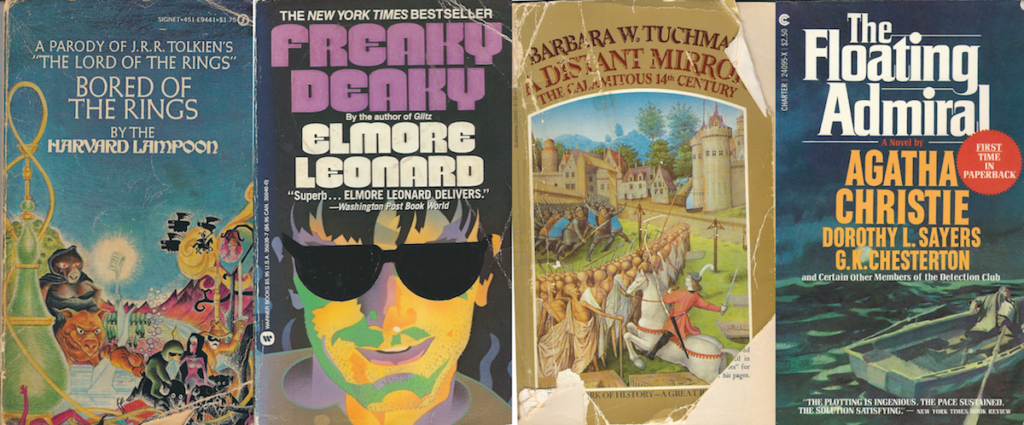

Photo credit: Krynowek Eine [el Eine]

--

Looking for more help on the craft of fiction? Check out our Elements of Fiction series:

- Beginnings, Middles, and Ends by Nancy Kress

- Scene & Structure by Jack Bickham

- Description by Monica Wood

- Plot by Ansen Dibell

- Characters & Viewpoint by Orson Scott Card

- Conflict, Action, and Suspense by William Noble

Also—get your work critiqued by a Writer's Digest instructor over at WritersOnlineWorkshops.com. Voice and Viewpoint starts this month!Save 15% with the code FEB10.

Jane Friedman is a full-time entrepreneur (since 2014) and has 20 years of experience in the publishing industry. She is the co-founder of The Hot Sheet, the essential publishing industry newsletter for authors, and is the former publisher of Writer’s Digest. In addition to being a columnist with Publishers Weekly and a professor with The Great Courses, Jane maintains an award-winning blog for writers at JaneFriedman.com. Jane’s newest book is The Business of Being a Writer (University of Chicago Press, 2018).