No Description Dumps! Crafting a Story With Details & Immersion

Today’s guest post is by Jim Adam. It is part of a series on storytelling and The Strengths of the Potter Series. Check out Jim’s book, Motherless.Rowling’s boxes of notes…

Today's guest post is by Jim Adam. It is part of a series on

storytelling and The Strengths of the Potter Series. Check out Jim's

book, Motherless.

Rowling’s

boxes of notes for the Potter universe are legendary. Those notes

translated into highly detailed characters and settings that captivated

readers. As much as the details themselves, Rowling’s careful selection

of which details to use—and which to exclude—illuminated the story

world without derailing the flow of the story itself.

Generally,

when a major character appears for the first time in the Potter series,

they receive one paragraph dedicated to their physical description—a

description that often ties into that character’s personality.

These descriptions never degenerate into a bland list of details, nor are these mechanical “head to toe” descriptions.

Instead, the descriptions pick a select number of key features which,

taken together, allow readers to form a mental picture of the person in

question.

The first description of Harry, for example, covers

the color of his hair and eyes, his glasses (held together with tape),

his scar, and his scrawny build—accentuated by his hand-me-down

clothes. Even though this is Harry we’re talking about, his physical

description doesn’t appear the moment we meet him. Instead, we first

see Harry waking up in his closet, dusting off a coating of spiders,

getting dressed, and being ragged on by Aunt Petunia. Only then does

the story pause to describe his appearance.

Also, the story

uses this first bit of description to point out that Harry’s life has

been a difficult one. The tape on his glasses is there because Dudley

picks on him. His scrawny build might have something to do with living

in a cupboard. His hand-me-down clothes imply an impoverished

childhood, one where Harry is a second-class citizen in the Dursley

home.

Another key feature of Harry’s appearance, his unruly

hair, comes out not in the first bit of description, but several

paragraphs later, in response to Uncle Vernon’s telling Harry to comb

his hair. Here again, a descriptive passage is made to do double duty,

this time illustrating Harry’s relationship to his uncle (the passage

focuses not on the exact appearance of our hero’s hair but on how his

unruly hair makes his life difficult).

By weaving

details in as part of ongoing action, the Potter series keeps those

details from being distracting. Instead, the descriptions become a

natural part of the flow of events.

Settings

receive a similar treatment. Minor settings, such as the Reptile House,

are described in a few sentences—enough to ground the reader, but

without belaboring a setting that will appear only once in the story.

This understanding of proper emphasis is another sign of an author who

knows what story she’s telling, who recognizes what is central and what

is ancillary, and who consciously places emphasis on key characters and

settings, not letting minor figures distract the reader or delay the

progress of the story.

As for a major setting like Hogwarts, details still aren’t dropped on the reader in a single blob. Instead, they filter out as needed.

We gets hints about the school when Hagrid makes his appearance at the

cottage on a rock. A few more tidbits come out during the trip to

Diagon Alley, where Harry first hears about Quidditch and the four

school houses. Then, when Harry first lays eyes on Hogwarts, the event

is covered in a single sentence! This again shows that the goal is to

keep the story moving forward, rather than reveal how much research the

writer has done.

What we see in the Potter series is not only a

depth of detail, but also a solid control over those details.

Descriptions don’t necessarily appear the moment a character or setting

is encountered, and most descriptions are dribbled out over time rather

than plopped down all at once. The result is that the Potter universe

feels layered and immense, yet the reader never feels overwhelmed or

bored. This is how it is supposed to be done!

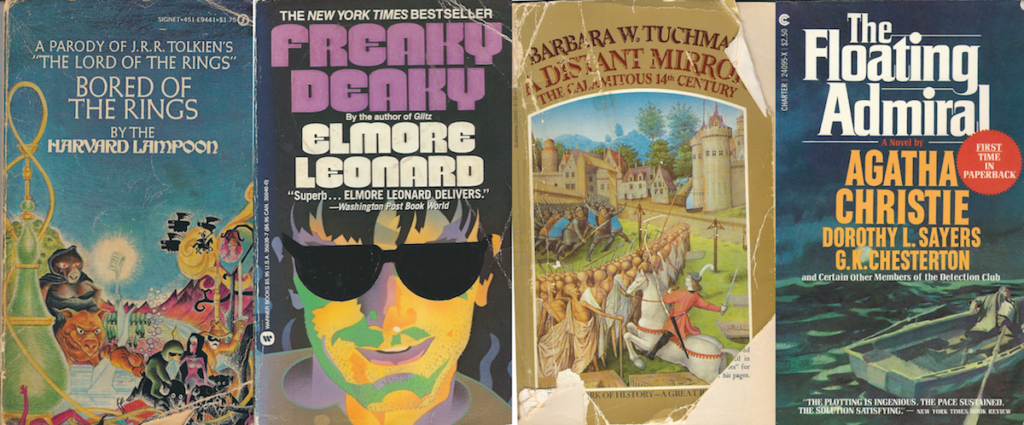

Looking for more help on the craft of fiction? Check out our Elements of Fiction series:

- Beginnings, Middles, and Ends by Nancy Kress

- Scene & Structure by Jack Bickham

- Description by Monica Wood

- Plot by Ansen Dibell

- Characters & Viewpoint by Orson Scott Card

- Conflict, Action, and Suspense by William Noble

Jane Friedman is a full-time entrepreneur (since 2014) and has 20 years of experience in the publishing industry. She is the co-founder of The Hot Sheet, the essential publishing industry newsletter for authors, and is the former publisher of Writer’s Digest. In addition to being a columnist with Publishers Weekly and a professor with The Great Courses, Jane maintains an award-winning blog for writers at JaneFriedman.com. Jane’s newest book is The Business of Being a Writer (University of Chicago Press, 2018).