Story Structure: Beginnings, Middles, and Ends

Today’s guest post is by Jim Adam. It is part of a series on storytelling and The Strengths of the Potter Series. Check out Jim’s book, Motherless. Structure is the…

Today's guest post is by Jim Adam. It is part of a series on

storytelling and The Strengths of the Potter Series. Check out Jim's

book, Motherless.

Structure

is the way scenes are organized so as to provide a clear beginning,

middle, and end to a story. For the Potter series, both individual

books and the series as a whole demonstrate a mastery of story

structure.

For one thing, the Potter stories are strongly

sequential. While we do get a few flashbacks here and there (via the

Pensieve and Riddle’s Diary), we certainly don’t get very many.

None of the stories has a Prelude that shows us events from the middle or near the end of a book. While

Preludes are a useful mechanism, beginning writers seem to use them

excessively, perhaps hoping to make up for a weak first chapter.

Nor

do the stories bounce us around within the timeline of the story. Even

Book 3, Prisoner of Azkaban, uses its time travel device in a

controlled manner, so that the linear, sequential feel of the storyline

is never compromised.

The school calendar also provides a

natural structure to each story. While this scaffolding becomes an

obstruction in the later books, still we have to acknowledge that all

of the books (but most especially the early ones) benefit from

connecting key plot events to calendar events. Each book begins at or

near Harry’s birthday, during the transition from summer vacation to

the start of the school year. Plot intensity ratchets up on key dates

such as Halloween, allowing each book to reach a solid middle point

during the winter holidays. From there, events move to their inexorable

close at or about finals week.

Not every story can have something as congenial as a school calendar to leverage, but many novels seem not to have any sort of grounding schedule at all. As a result, readers begin to wonder, “Is this story going somewhere? Or will it just continue to flop around aimlessly?”

The

Potter series uses the school calendar to emphasize the beginning,

middle, and end of each story. As a result, events feel more connected,

heightening the reader’s sense of, “The shinbone is connected to the

thighbone, The thighbone is connected to the hipbone.” Another way of

saying this is that the school calendar helps to telegraph the

structure of the story, but without giving away any surprises.

A

telegraphed structure tells readers “This story is heading somewhere,”

without producing a sense of, “Oh, I know exactly where this is going.”

As such, the school calendar is a win-win solution, with but a single caveat: that it might get overused.

The

Potter series as a whole also has a clear structure, one that readers

are at least subliminally aware of. We don’t know exactly what will

happen, but as we read, we have a sense that each book is right for its

place in the series. In Book 3, Prisoner of Azkaban, Voldemort’s return

becomes imminent. In Book 4, Goblet of Fire, his return is realized. In

Book 5, Order of the Phoenix, he manipulates events from the shadows.

In Book 6, Half-Blood Prince, he steps out into the open.

Thus,

unlike many series, the books of the Potter series aren’t basically

interchangeable. Books 1 and 2 form a clear beginning. Books 3 through

6 steadily escalate the conflict, while Book 7 brings the series to its

climactic end.

For readers, this all feels right and correct,

without feeling predictable. This is because the series manages to

telegraph its structure without telegraphing the plot.

Finding the Beginning

Finding

the beginning of a story is probably the most difficult task for a

writer, as far as story structure is concerned. Consider Book 1 of the

Potter series, Philosopher’s Stone, which starts shortly after the

death of Harry’s parents and the disembodiment of Lord Voldemort. Is

this the true beginning of the story? It seems so.

Imagine

omitting the first chapter of Book 1. This would leave readers in the

dark as to Harry’s true nature, so that the torments he suffers at the

Dursleys’ wouldn’t mean as much. Moreover, readers would be wondering

not just “what is going to happen next,” but “what is this all about?”

Some readers are more patient than others, but by revealing Harry’s

true nature up front, along with his connection to the mysterious

wizarding world, Book 1 caters to even those of us who have limited

patience for directionless, “try to guess what I’m thinking now” prose.

Similarly,

Harry’s experiences at the Dursley home are important to our

understanding of him as a person. They let us become attached to him,

and give us insight into what kind of person he is. Thus, to start Book

1 with Harry boarding the Hogwarts Express wouldn’t cut it. Yes,

boarding the train is a powerful moment, and it marks the spot where

the book really takes off. But the train scenes would lose much of

their significance if we were strangers to Harry, having only just met

him.

In sum, it seems unwise (or at least fruitless) to try and start Book 1 at a later time in the narrative.

Could

it start earlier? In this case, not very easily. The opening of Book 1

could certainly be jazzed up, by exchanging its current focus on Vernon

Dursley with something more Harry-specific, such as his being retrieved

from Godric’s Hollow by Dumbledore and Hagrid. But to start the book

with Harry’s parents still alive would be a mistake. Readers would be

introduced to two people who immediately get killed. If Book 1 were

meant to be primarily a horror story, such an approach might be

appropriate, but even so, it would introduce a BEGIN ... END ... BEGIN

quality to the very start of the book—and some readers might be put

off, never getting past that second BEGIN.

Finding the right

place to begin a story can be a thorny problem, but Book 1 makes the

perfect choice, however difficult. It resists the urge to start with

Harry’s parents still alive, though this means giving up an emotionally

powerful scene, with Lily sacrificing herself to save Harry; as a

result, Book 1 avoids adding a false start quality to the narrative.

The

book also resists the urge to skip forward and start with Harry living

at the Dursley home, even though the current first chapter gives away

important information regarding Harry’s identity and the true nature of

the world he lives in. (An insistence on secrecy at all costs—a

fanatical devotion to surprise—would have left out Chapter 1, and would

have made the opening of Book 1 feel pointless to many readers.)

Book

1 also resists the urge to start with Harry boarding the Hogwarts

Express, giving up an energetic, in medias res opening, in favor of a

more linear storyline that increases the feeling of

beginning-middle-end in the book as a whole, and allows for a

suspenseful buildup toward a powerful Bright Moment in the first

quarter of the book.

Middle and End

With a beginning

solidly in place, middle and end become a question of alertness. So

long as the writer has a story to tell, and is telling that story, they

need only ask themselves at regular intervals:

“When was the last time the plot moved forward? When was the last time the intensity ratcheted up?”

In

a long work such as a novel, the pace and intensity will naturally rise

and fall, and subplots will occasionally take center stage. But so long

as the writer remains alert, such things present no danger. Quidditch,

romance, friendship, hobbies, and even day-to-day events can all play

their part. Only when ancillary events derail the plot for long

stretches, or subvert the plot entirely, only then do they become a

problem.

Particularly in the early books, the Potter series

demonstrates a mastery of interweaving subplot with plot. The first

Quidditch game is more than an action sequence, as it introduces a

threat to Harry’s life. Chess games in front of the Gryffindor

fireplace become significant later when the Big Three are trying to

reaching the chamber where the philosopher’s stone is hidden. Harry’s

parselmouth ability makes his life difficult in the near term,

ratcheting up the conflict, and it later becomes essential to the plot,

as it allows him to open the Chamber of Secrets.

In sloppy

commercial fiction, scenes often too fail to advance the story, making

a novel feel like it is spinning its wheels or driving around

aimlessly. By contrast, the Potter series is constantly moving forward,

with readers convinced that the direction of movement makes perfect

sense, no matter how surprising a development might be.

Because individual scenes clearly serve the story, readers are left eager for more.

Next in series: Premise vs. Story

--

Looking for more help on the craft of fiction? Don't miss these offerings:

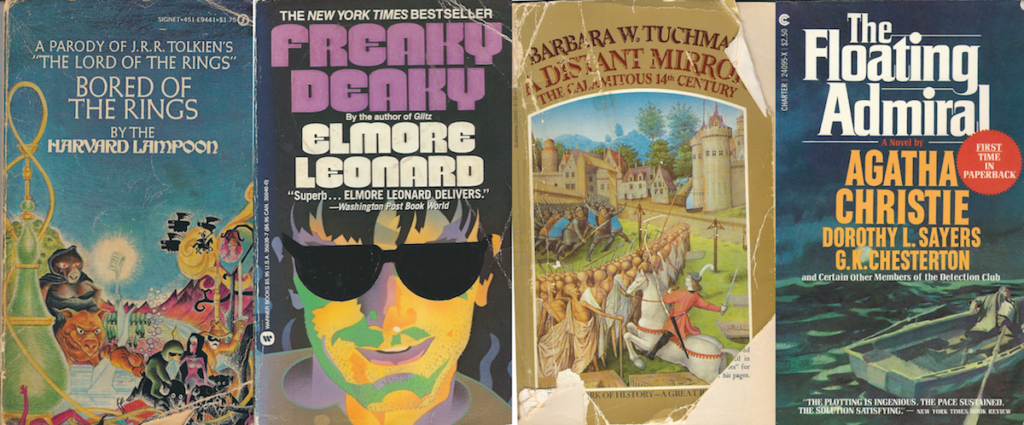

- Check out one of our best titles in the Elements of Fiction series:

Beginnings, Middles, and Ends by Nancy Kress - A longtime favorite of fiction writers:

Story Structure Architect by Victoria Schmidt - Take an online course and get feedback from a professional and published instructor. Here's one of my favorites on plot & structure. (Use coupon code JAN10 to get 15% off.)

Jane Friedman is a full-time entrepreneur (since 2014) and has 20 years of experience in the publishing industry. She is the co-founder of The Hot Sheet, the essential publishing industry newsletter for authors, and is the former publisher of Writer’s Digest. In addition to being a columnist with Publishers Weekly and a professor with The Great Courses, Jane maintains an award-winning blog for writers at JaneFriedman.com. Jane’s newest book is The Business of Being a Writer (University of Chicago Press, 2018).