Mastering Puzzles: How Dyslexia Made Me a Better Writer

Author Amanda Ann Gregory shares how dyslexia has made her a better writer.

In elementary school, I wrote precocious essays inspired by movies and proudly handed them to my teachers. I wrote about why Shoeless Joe Jackson shouldn’t have been banned from baseball (Field of Dreams), why Virgil Earp deserved more credit for his role in the fight at the O.K. Corral, as he was overshadowed by his more famous brother Wyatt (Tombstone), and how sharks, often misunderstood, deserve more respect from humans (Jaws). I received A’s on every essay, but my teachers were confused because my passion for writing didn’t translate into an appreciation for reading.

Throughout my childhood, I despised reading. I didn’t read any assigned books in school and refused to read aloud. In 5th grade, I asked my teacher if I could write a book instead of reading Charlotte’s Web. She agreed, thinking I would learn that writing a book was much more challenging than reading one. She was wrong. I turned in a handwritten book with illustrations about the social structure of a township of spiders living in a woman’s hair. I received an A, but my teacher recommended I meet with the school counselor for testing after noticing I often switched the letters p, q, b, and d. The tests revealed that I was dyslexic, and that’s when my journey of learning to embrace my strengths as a dyslexic writer began.

Seeing Words

I struggle to interpret auditory information, making it difficult to ‘hear’ the meaning of words. While I can hear the sounds of words, they carry little meaning. I don’t listen to audiobooks or podcasts because I find it difficult to understand and retain the information. Reading aloud is challenging because no pre-existing meaning is attached to auditory words. This ‘deafness’ to words can be a barrier, but like many people who lack access to one sensory experience, I have developed another heightened sense to compensate.

I have an advanced sense of word sight. I can see, touch, and manipulate words, almost like puzzle pieces that can combine to form endless combinations. To decode the meaning of words that I hear, I write them down, translating them into a visual form. Once I can see them, I can easily manipulate them. Dyslexia has given me this unique gift of word sight, which has prevented me from ever experiencing writer's block. There are always words to be seen, so writing always feels possible.

Embracing Movement

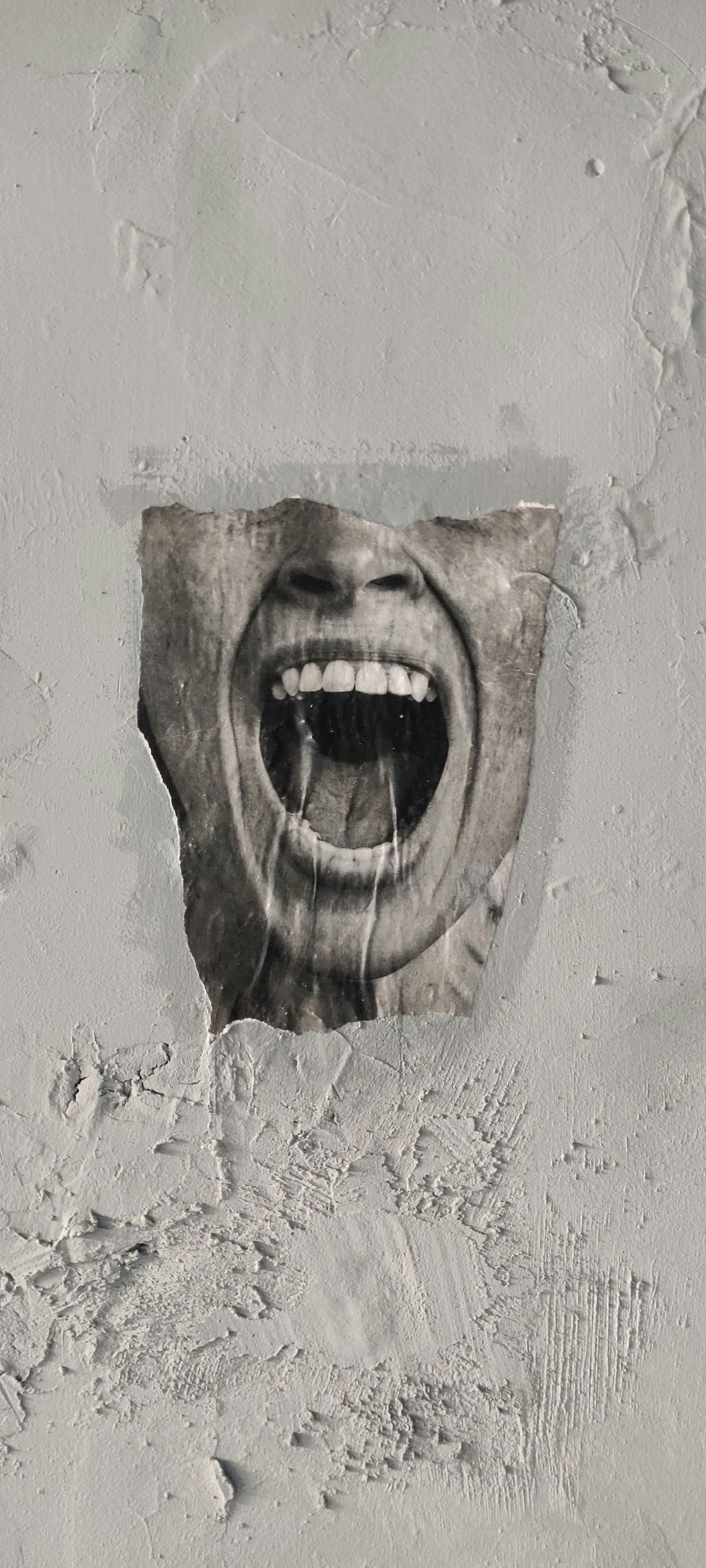

Words are constantly moving, much like water. They can quickly change forms as water becomes liquid, gas, or solid. Dyslexia allows me to observe this movement in real time as I watch Ds become Bs and letters appear and disappear randomly. While I can eventually correct these shifts by turning Bs back into Ds and fixing spelling errors, when I’m writing, I accept the fluidity. Seeing fictional alterations of words has made me a more flexible and adaptable writer. I am not restricted by rigid rules, knowing that letters and words cannot remain still, no matter how hard I try to force them.

Recognizing this movement is one thing, but learning to embrace it took years. I eventually learned to stop resisting the word waves, urging me to float with them rather than swim against their currents. Once I let go, I experienced significant growth as a writer. I now watch my words connect seamlessly, like perfect puzzle pieces, refusing to be separated. When this happens, I leave them alone. I also observe when my words break apart and flee in all directions, resisting forced connections. When this happens, I let them go their separate ways without prejudice. I notice when sentences hover, signaling that theyneed to be moved, and I shift them. I can see when a word, sentence, or entire chapter no longer fits, and instead of clinging to it, I let it float away.

Creating and Solving Puzzles

Writing has never felt like an accurate description of what I do. I’m more of a puzzle maker and solver. My first book, You Don’t Need to Forgive, was a massive jigsaw puzzle comprising thousands of pieces I created over three years. Every research article, quote, case study, and personal experience became a piece. Creating pieces is chaotic, especially when I need to see all the pieces before I can connect them. Hundreds of written index cards were taped to my walls, books vandalized by highlighters were piled on my desk, and trails of bits of crumpled-up paper lay on the floor in my office. This tedious process was necessary to create all the pieces I needed to solve my giant puzzle.

When I begin a jigsaw puzzle, I sort all the pieces into colors and shapes (edges and non-edges). I do the same when I write, organizing pieces by content and flow. As I sort them, I can spot pieces that don’t fit, allowing me to edit early. I never struggle with ‘killing my darlings’ because my darlings choose to leave on their own. Instead of forcing them to stay, I respect their wishes and let them go.

I allow my pieces to show me where they belong by embracing their movement. Whenever I feel stuck, I step back, observe, and only respond when I see how the pieces move. As my pieces connect, they form clusters of sentences and paragraphs that eventually come together as chapters and, finally, a book. The puzzle might be complete, but I know it will continue to move long after the pages are published.

Strengths of a Dyslexic Writer

A dyslexic writer might sound like an oxymoron, but these two pieces fit together beautifully. I can’t hear words, but I see them with a heightened sense of sight. While my perception of word movement turns my Ps into Qs, it also makes my writing fluid and adaptable. I cannot spell to save my life, but I will never run out of ideas. My hundreds of cluttered pieces are chaotic and unstructured, but they will soon become organized and proactively edited as they are pieced together.

Dyslexia isn’t a curse; it’s simply a different way of learning, and it has improved my writing far more than hindered it.

Check out Amanda Ann Gregory's You Don't Need to Forgive here:

(WD uses affiliate links)

Amanda Ann Gregory is a trauma psychotherapist renowned for her work in complex trauma recovery, notably as the author of You Don’t Need to Forgive: Trauma Recovery on Your Own Terms. With a keen focus on the specific needs of trauma survivors, Gregory’s expertise spans over 17 years in clinical practice. She has been featured in The New York Times, National Geographic, and Newsweek and published in Psychology Today, Psychotherapy Networker, Highlights for Children, and five Chicken Soup for the Soul books. She lives in Chicago, Illinois, with her partner and their sassy black cat, Mr. Bojangles.