Crafting a First-person Essay

From choosing a topic to weighing your words, here’s a start-to-finish guide to writing an essay that makes a clear point without skimping on personal insight.

First-person essays span space, time and subject: The city dump, an obsessive bird or a toy from the '60s—all subjects of essays I've published—can come up with just one shuffle of an endless deck of compelling themes. Mongrel lot or not, it's never the subject of an essay that tells, but the style and stance of its author. What might seem the least likely of essay subjects can be made riveting or poignant with just the right touch. We'll look here at choosing the topic, slant and voice of your essay, constructing a lead, building an essay's rhythm and packing a punch at the essay's end.

TACKLING A TOPIC

Because one of the great appeals of the personal essay is the conversational tone essayists take, it seems a given that it's best to be conversant with your subject. But "write what you know" can also be an inkless cage; some of the best essays are a voyage of discovery for both writer and reader. You might accidentally flip some breakfast cereal with your spoon and have an epiphany about the origins of catapults. That little leap might take you seven leagues into the history of siege engines and voilaé! A piece for a history journal comparing ancient weapons to new.

Subjects float all around you. Should you write about baseball, bacteria or bougain-villeas? The key is engagement with your topic so the angle your writing takes is pointed and penetrating. You don't write about cars; you write about the fearful symmetry of a 1961 T-Bird. The essayist should be (to paraphrase Henry James) one of the people on whom nothing is lost. Idly looking over at a fellow driver stopped at a traffic signal might be a moment to yawn, but it might also be a moment to consider how people amuse themselves in their vehicles. An essay here about new car technology, an essay there about boredom and its antidotes.

Essays are literally at your fingertips. Consider a piece on how fingerprint technology evolved. Or at your nosetip: My most recent published essay was about a lurking smell in my house that led to a mad encounter with attic rats. Humble topics can spur sage tales. Annie Dillard's recounting of seeing a moth consumed in a candle flame morphs into an elegy on an individual's decision to live a passionate life. You don't need glasses to find your topics—just a willingness to see them.

SLANT AND VOICE

Which way should your essay tilt? Some essays wrap blunt opinions in layered language, ensnaring a reader with charm, not coercion. Louis Lapham's essays often take a political angle, but any advocacy is cloaked in beguiling prose. Personal-experience or "confessional" essays done well deftly get away with impressionistic strokes: words evoking sensations, scents and subtleties. Consistency in tone is compelling; leading your reader through your essay with sweet conceptual biscuits only to have them fall hip-deep in a polemical cesspool at essay's end is counterproductive.

Essays are personal—the best of them can seem like a conversation with an intelligent, provocative friend, but one with remarkable discretion in editing out the extraneous. Whether the word "I" appears at all, you must be in your essay, and pungently. It can't be simply "How I Spent my Summer Vacation"; it must be "How I Spent my Summer Vacation Tearfully Mourning my Dead Ferret." Never hide in an essay. Essays aren't formless dough. They're the baked bread, hot and crusty. Cranky, apprehensive or playful, your candid voice should be a constant. You don't want your essays to roar like a lion in one paragraph and bleat like a mewling lamb in another (unless it's done for effect).

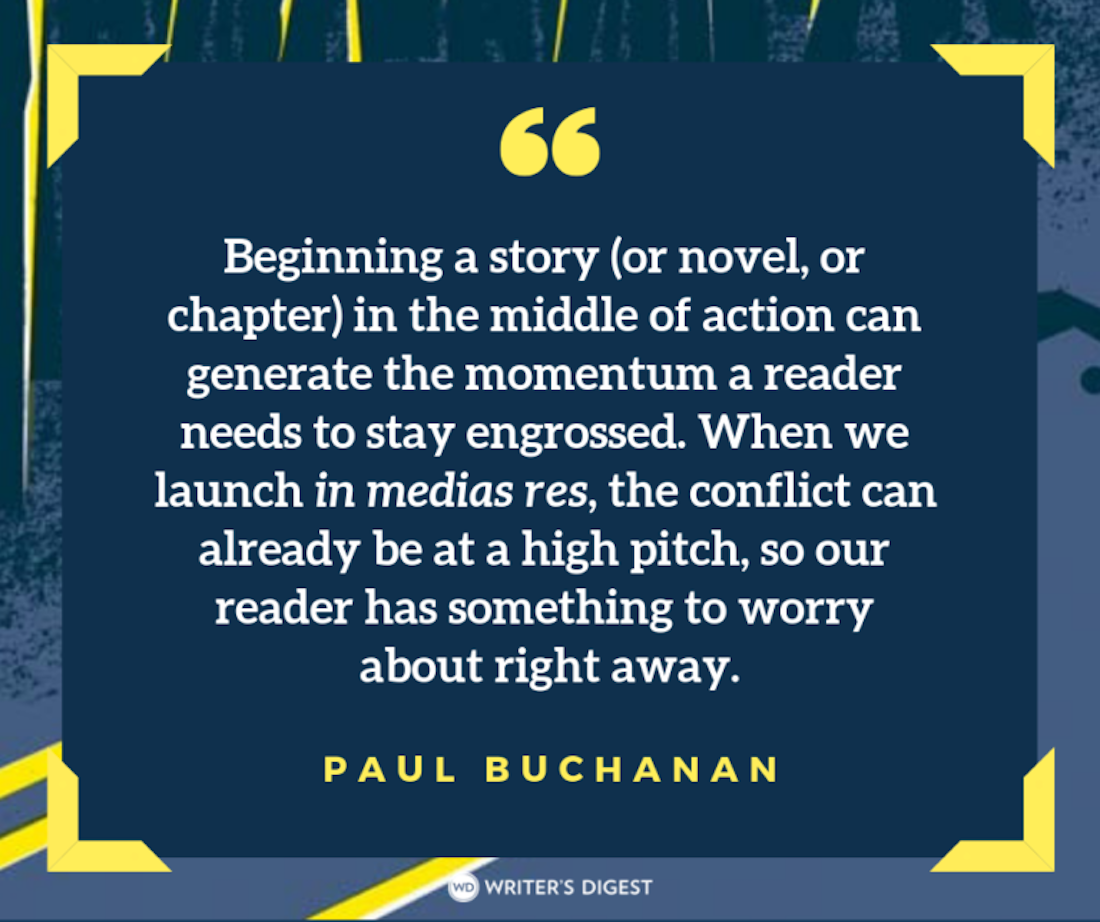

LEAD OR LOSE

Leads are big. If your first bite of a meal is bland, you're likely to put the fork down and call for takeout. You've got to grab readers from the get-go. One method is direct address. Here's the lead from an article of mine about dictionaries:

Think of your favorite book. No, better yet, go and get your favorite book, feel its heft in your hand, flip through its pages, smell its bookness. Read a passage or two to send that stream of sparks through your head, the alchemy that occurs when the written word collides with the chemicals of your consciousness. Delight is the fruit of that collision.

It tells the reader to do something, with a visual and sensual context. It's difficult to read that lead and avoid doing what it requests, at least in your imagination.

Here's another lead of mine that takes a different tack, one of identification or empathy:

Scuttlebutt had it that Barbara Cartland, the doyenne of romance writers, did much of her early writing at the piano, stark naked. However that strains credibility, everyone's heard of writers who insist they can't write without their ancient manual typewriters with the missing keys, or their favorite fountain pens (or maybe even a stylus and hot wax). Writers can be a peculiar lot, and it's not surprising that their composing methods can be all over the map.

Besides beginning with a memorable image of Cartland, the essay invites readers to consider their own fetishes and peccadilloes about favorite objects. You want the reader here to nod yes, agree that people are odd, and move forward into the piece.

Sometimes a question that has a universal appeal can accomplish this:

Could listening to a barking dog actually drive you mad? I fear it could. Worse yet, I fear this not in theory, but in fact: Barking dogs are making me a sweaty mess.

The statement shapes my own problem into one that might apply to many. You'll drag a dog lover or hater (and that's a broad audience) deep into the essay by this lead leash.

STRUCTURE AND RHYTHM

Most essays aren't built on journalism's inverted pyramid, stacking essential information upfront and moving to leaner layers as factual momentum fades. Instead, essays often take elliptical paths that meander around in a subject's fields, picking its flowers, discarding them, looking to metaphoric hills beyond and then up close at the ground below. An accomplished essayist like Edward Hoagland wends his way through paragraphs, often taking a quick conceptual turn that might seem a misstep or dead end. But he always re-establishes his rhythm, much like a jazzman vamping and then returning to the deeper theme.

Hoagland is a good study on the magic of cadence and the musicality of words; he makes the difficult art of weaving layered points of view with bright language seem easy. That's not to say that a more straightforward path through your essay isn't the best course. Mark Twain's "The Private History of a Campaign That Failed" essentially plots a chronological rendering of the hapless—and hilarious—exploits of a band of Civil War bumblers, Twain prominent among them.

Determine if your material is the sort that should sneak up on readers to win their trust or overwhelm them with the sustained march of topic vigor. I wrote an essay about an old California beachside amusement park that alternated paragraphs (and sometimes sentences) about the checkered history of the park with paragraphs of my own wide-eyed history of teenage entanglements there. That old/new juxtaposition gave a flow to the piece that worked much better than "Here's the Pike's history, and then here's what it was like when I was a kid."

In contrast, I started out a piece on the death of my cat with a dramatic accounting of his final moments and used that emotional tocsin to resonate through every paragraph, sifting the sense of loss. Your material probably has an organic flow—try to see how ideas connect and separate.

WRAPPING IT UP

Just as a good lead hooks readers and draws them along for the ride, a good conclusion releases them from your essay's thrall with a frisson of pleasure, agreement, passion or some other sense of completion. Circling back to your lead in your conclusion is one way to give readers that full-circle sense. Try to restate your thesis in a way that reflects the journey the essay has taken.

Only if you have subtle skills can you leave your readers hanging on an ambiguity or wondering at your waffling. Readers want customer satisfaction, and essays that have a "new fiction" inconclusiveness don't scratch that itch. Unless, of course, you can construct the kind of conclusive inconclusiveness of the last paragraph of H.L. Mencken's "Imperial Purple":

Twenty million voters with IQs under 60 have their ears glued to the radio; it takes four days' hard work to concoct a speech without a sensible word in it. Next day a dam must be opened somewhere. Four Senators get drunk and try to neck with a lady politician built like a tramp steamer. The Presidential automobile runs over a dog. It rains.

Whether you annoy them or astound them, leave your readers with something of yourself. They'll return to your writing hungry for more.

Tom Bentley lives in the hinterlands of Watsonville, California, surrounded by strawberry fields and the occasional Airstream. He has run a writing and editing business out of his home for more than 10 years, giving him ample time to vacuum. He’s published over 250 freelance pieces—ranging from first-person essays to travel pieces to more journalistic subjects. He is a published fiction writer, and was the 1999 winner of the National Steinbeck Center’s short story contest. See his writing-related blog here. His new collection of short stories, FLOWERING, AND OTHER STORIES is now available.