6 Writing Lessons from Alfred Hitchcock’s Rear Window

It has gotten to the point where I can’t watch a film or TV show, read a book, listen to a song, or play a video game without thinking…What can…

It has gotten to the point where I can’t watch a film or TV show, read a book, listen to a song, or play a video game without thinking…What can this teach me about writing? A recent viewing of this Hitchcock classic brought a few lessons to the forefront of my mind.

Spoiler Alert: Please note that I’m taking for granted that you’ve seen the film, so if you haven’t, please rush out and watch it now…and then come back and enjoy these craft suggestions spoiler-free! Otherwise the following will reveal some important plot points. Reader beware!

1. When in Doubt, Cast Doubt

There is a great scene not long after our wheelchair-bound protagonist and professional nosey neighbor, L.B. Jefferies (James Stewart), becomes suspicious of his neighbor Thorwald (Raymond Burr). He observes his neighbor’s strange activities throughout the night, but is asleep during a key scene when Thorwald (whom Jefferies suspects killed his wife earlier that evening) is seen leaving his apartment with another woman just before dawn. Is Thorwald’s wife actually dead? Is Jefferies wrong about Thorwald? Just what does this scene do for us, the viewer?

First and foremost, it plants the seed in our mind that maybe our protagonist is about to harass and accuse an innocent man. And because Jefferies misses out seeing the mystery woman, he is still sure of himself that Thorwald did away with his wife in the night.

Granted, if he wasn’t asleep in that key moment, the movie could have ended right there. “Oh, there she is. All is well.” THE END

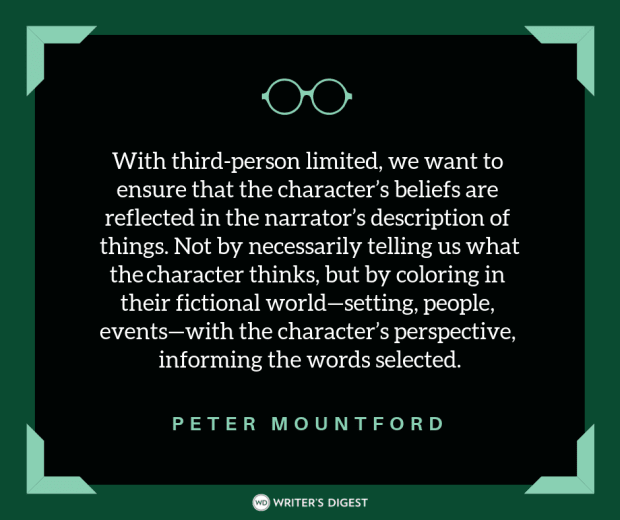

But all wasn’t well, was it? Allowing the reader to know more or different information than the protagonist is an excellent way to build suspense—and if anyone knew how to do that, it was Hitchcock! You can do the same by jumping to another scene without your primary characters and let other events unfold unbeknownst to your hero or heroine—one of the simple, more well-known powers of a third-person narrative. But it can be done in the first person POV as well by simply omitting a key detail and/or presenting facts that counter your protagonist’s line of thinking through secondary characters and hearsay. By introducing these conflicting pieces of evidence, we will find our protagonist toiling away on a “case” while we are on the edge of our seats, wondering if the protagonist is correct despite evidence that blurs the truth of the matter, or if the protagonist is going to end up in a very embarrassing and perhaps deadly situation for no reason at all aside from a hyperactive imagination.

2. Pile on the Doubt With Doubters

Nobody believes Jefferies, at first. Thorwald displays one odd habit after another, and Jefferies has to bend over backwards (hard to do in a full leg cast!) to convince his beautiful and fashionable girlfriend, Lisa, played by the one and only Grace Kelly, that he's right. His old war buddy, now a detective, doesn’t believe him either, mostly because all of the evidence he’s able to find on Thorwald clears his name. Time after time, Jefferies seeks out the law for help and is rebuffed by facts and common sense until his friend finally tells him to lay off and mind his own business.

Does he? Of course not. Every doubter only serves to make Jefferies MORE convinced that he’s right. So feel free to throw speed-bumps in front of your own protagonist, and remember that they’re even more effective when they come from trusted allies and cast logical, reasonable doubt on each one of your protagonist’s suspicions.

3. Trick-or-Trait!

Just like every costumed kid who knocks on your door at Halloween gets a piece of candy, every minor character in your book deserves a trait. And Rear Window is full of minor characters, each fully brought to life with almost no dialogue at all. You have Miss Lonelyheart, a wistful middle-aged woman desperate for love; Miss Torso, the dancer across the courtyard who lives above a deaf sculptor who lives across from a musician constantly working on a piano composition who can look out his window and see another neighboring couple who sleep on their fire escape and own a small, nosey dog…one after the other after the other. With just a few unique details, Hitch brings a character to life and makes them memorable.

Consider your own characters and give them a twist…maybe that clerk at the DMV is deaf or is known for his lopsided hairpiece, maybe the sister-in-law at the funeral has a troublesome pet ferret, maybe the protagonist comes home each day to find the babysitter filling the house with music as she practices the viola. One or two unique traits can make minor characters stand out to a reader and can make your main characters look lazy, kind-hearted, nosey, intelligent, or pedantic by comparison. Writing a novel is like making chili in a crockpot—everything adds a little flavor and affects the final result, so have fun with the minor details.

4. All Five Senses Builds a Fine Atmosphere

The atmosphere Hitchcock builds throughout this film is genius. We hear music coming from other apartments, rain falling at night, street noise, dogs barking; we see each neighbor’s activities through their windows as well as sunsets, stormy clouds, and even Hitchock himself; we can almost taste and smell that lobster dinner Lisa brings for Jefferies, the brandy swirling in their snifters as they entertain guests, the smoke from the cigar Thorwald puffs upon while he sits in the dark of his apartment; we can feel the itch Jefferies cannot scratch while in his cast, the vertigo (oh, James Stewart and his vertigo problems) he feels when dangling from his window, the stinging, blinding light Jefferies flashes to ward off a murderous Thorwald. Every sense and emotion is engaged in this film, creating a brilliant symphony of real life. So as you look at the scenes you built in your novel, ask yourself, “What detail have I left out during the hundreds of times I have imagined this story before? What one wrinkle can I unfold to reveal a new emotion, sense, or detail in order to build the atmosphere I desire?” Consider this question scene by scene, chapter by chapter.

5. Location, Location, Location!

The entire story takes place in Jefferies apartment as he looks out his rear window. Yes, Hitchcock could have shown the detective friend going to the train station to talk to witnesses, or could have followed Lisa into Thorwald’s apartment through her own point of view (which might have been terrifying but no more so than seeing Thorwald approach little to her knowledge). But no, everything Hitchcock needed was right there in that courtyard, visible through Jefferies’ windows. And while that might seem like a gimmick, there are countless one-act plays and short stories that do the same, even some novels (Murder on the Orient Express comes to mind). And while you don’t need to have just one location, you DO need to have a good one, or many good ones. Your location can make or break your novel, so make sure you’ve selected the right place for your characters, a place that will bring out their best or worst qualities, a place that might hinder their ability to be a reliable narrator or a fully-aware character, a place that will push them out of their comfort zone. Challenge them with a unique setting!

6. Juxtaposition is SO Romantic

The romance between Jefferies and Lisa is strained and strained again because they just don’t seem right for each other. Jefferies is a rough-and-tumble adventure photographer who feels at home in a muddy jeep while Lisa is a fashionable New York socialite who is always (and I mean always) dressed to the nines. He constantly tells her that she’s too good for him and that he’s not made for her clean-cut world. But his longing glances when she leaves at night and the horrified concern he shows for her when she’s in danger (as well as the admiration he exhibits when she survives) clearly shows us that these two may not be peas in a pod, but there’s a lot of love there.

And different as they may be, they each have what the other needs in life. Jefferies may not like to admit how lonely he feels on the road and is amused by Lisa pampering him with dinners and visits, and Lisa finds both stability in the relationship (opting to spend a night eating in with him and keeping him company) and great pleasure from his adventurous mishaps. He's a challenging man, and as her character reveals over time, she's always up for a challenge. Her relationship with him breaks the mold of her very structured social lifestyle in New York. They’re polar opposites, and yet they fill the holes in each other’s lives.

Now imagine if he had been a real estate broker or a wealthy banker instead of a photographer. Or imagine she were a travel writer or a pilot instead of a socialite? They’d be as happy as clams, made custom for each other’s lifestyle, and they likely wouldn’t give a single thought about what’s happening outside their windows. Kind of dull, right? Instead, they’re pushed, confused, wounded, curious about what each other is thinking as well as how others around them live their lives...which leads to the murder mystery that unites Lisa and Jefferies for keeps. Their being opposites not only drives the plot, but their romance as well.

***Update: Let's not forget the excellent writing by screenwriter John Michael Hayes who based the screenplay on Cornell Woolrich's 1942 short story, "It Had to Be Murder." Thanks to the WD readers who pointed that out on Facebook!***

--

James Duncan is a content editor for Writer’s Digest, the founding editor of Hobo Camp Review, and is the author of the short story collection The Cards We Keep and the poetry collection Lantern Lit, Vol. 1. He is in the process of submitting a handful of novels to agents for traditional representation, just like everyone else on the planet. For more of his work, visit www.jameshduncan.com.